Timing the market is a typical beginners mistake. You’ve probably done it already. What does it mean to time the market? And why should you avoid market timing? Let’s find out.

What is market timing?

“There will be a correction in the next 3-6 months”. “Better to wait until prices drop further”. “We’ve seen the bottom already”. Sounds familiar? These are examples of market timing. Market timing relies on predictions of future market price movements as a basis for buying or selling decisions. It sounds great. There’s nothing like buying when markets are about to go up. Or selling before a market crash.

Why isn’t then every investment strategy all about market timing? Because it doesn’t work.

Why to avoid market timing

The main reason to avoid market timing is that there’s abundant evidence that it’s a fool’s game.

In general, it’s up to the proponents of a any claim to provide scientific evidence for it. Not up to the detractors to prove it wrong. If I tell you that investing during a full Moon increases returns, it should be up to me to prove it. Not up to you to disprove it.

However, detractors are ahead in the field of market timing. Maybe this is because you don’t need research to convince people to try to time the market. It comes to us naturally. You need research to convince people to avoid market timing, though.

The evidence against market timing

The table below aggregates findings against market timing from peer reviewed journals, universities and reputable companies. This is just the tip of the iceberg. But should give you an idea.

| Publisher | Year | Conclusion | Publication |

|---|---|---|---|

| Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis | 2014 | An average equity mutual fund investor tends to buy when past returns are high and sell otherwise [...] causing the average U.S. mutual fund investor to miss around 2 percent return per year | Chasing Returns Has a High Cost for Investors |

| Journal of Financial Economics | 1999 | Using a sample of more than 400 U.S. mutual funds [...] we find no evidence that funds have significant market-timing ability | Conditional market timing with benchmark investors |

| The Journal of Business | 1984 | The empirical results do not support the hypothesis that mutual fund managers are able to follow an investment strategy that successfully times the return on the market portfolio | Market Timing and Mutual Fund Performance: An Empirical Investigation |

| Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis | 2000 | Four tests of timing skill, carried out on a sample of 558 mutual funds, show that very few funds exhibit statistically significant timing skill | Monthly Measurement of Daily Timers |

| Financial Analysts Journal | 1991 | After-cost return from active management must be lower than that from passive management | The Arithmetic of Active Management |

| Boston College | 2017 | When fund managers attempt to boost returns by veering off the glide path, their decisions do not seem to help and may even hurt | Target date funds: what's under the hood? |

| The Wharton School | 2010 | [The model] reproduces the negative unconditional risk-adjusted performance of actively managed U.S. equity mutual funds | Why mutual funds ‘‘underperform’’ |

| DALBAR | 2016 | Investors who execute purchases or sales in response to something other than a prudent investment decision reduce the return created by the markets | 22nd Annual Quantitative Analysis of Investor Behavior |

| Banque Nagelmackers | 2018 | Market timing is detrimental to a sound and disciplined investment process | Market Timing: Opportunities and Risks |

| Blackrock | 2013 | In an ideal world, investors 'buy low, sell high.' Though the rule seems simple, we've often seen investors do the exact opposite, especially during volatile times | BlackRock chart of the week |

Funds vs retail investors

Notice that a lot of this research is conducted on funds. Funds are professional institutions. They have more money, more time and more knowledge than retail investors (you). And normally make less emotional decisions since they invest other’s money. Yet they consistently fail to time or outperform the market. Retail investors (you) face even worse odds.

Market timing and unbiased research

Research on market timing is controversial. This is because there are whole industries that depend on market timing to justify their existence. In the US alone, for example, there’s over 9,000 mutual funds managing over USD 18 trillion [1]. If passive investment is simply superior than active management, these companies have little point to exist.

If you decide to conduct your own research (which you should), make sure to focus on evidence presented by independent parties. Those with a steak in the game will be biased.

What experts say

Enough with the scientific evidence. What do investing gurus say about market timing?

I do not know of anybody who has timed the market successfully and consistently. I don’t even know anybody who knows anybody who has done it successfully and consistently.

Jack Bogle

I spent much of my career trying to devise a good formula for when to get into – and out of – the stock market. All formulas failed.

Benjamin Graham

The only value of stock forecasters is to make fortune-tellers look good.

Warren Buffet

Buy and hold.

Daniel Kahneman, after receiving the Nobel Prize and being asked for investment tips

Nobody can predict interest rates, the future direction of the economy or the stock market.

Peter Lynch

You can find additional quotes here.

So, will you try to time the market?

If you were a rational investor, this should be all you need. You should be convinced to avoid market timing. This entry could stop here.

Unfortunately, none of us is 100% rational. And, at times, you’ll think that you can time the market. Either explicitly or implicitly. Surely. 100%. Let’s repeat it again. Despite abundant evidence that you can’t, you’ll still think that you can time the market. You’ll find it difficult to commit to periodic, regular investments. You’ll find it difficult to never sell. Instead, you’ll think that it’s better to wait things out. Or to invest everything now. Chances are you’ll lose money in the way.

Because it’s still likely that you’ll try to time the market, I won’t stop here. Instead, I’ll share with you some additional, not-so-scientific perspectives on why to avoid market timing. These perspectives are rather personal, and independent from one another. I’ve gathered them over the years. And they’ve come handy in weak moments. I believe you’ll find powerful food for thought in them. Some might read a bit harsh. Keep in mind that I write to myself. Same as it’ll be for you, minimizing market timing has been a journey for me as well.

Perspective 1: Retail investors simply get it wrong

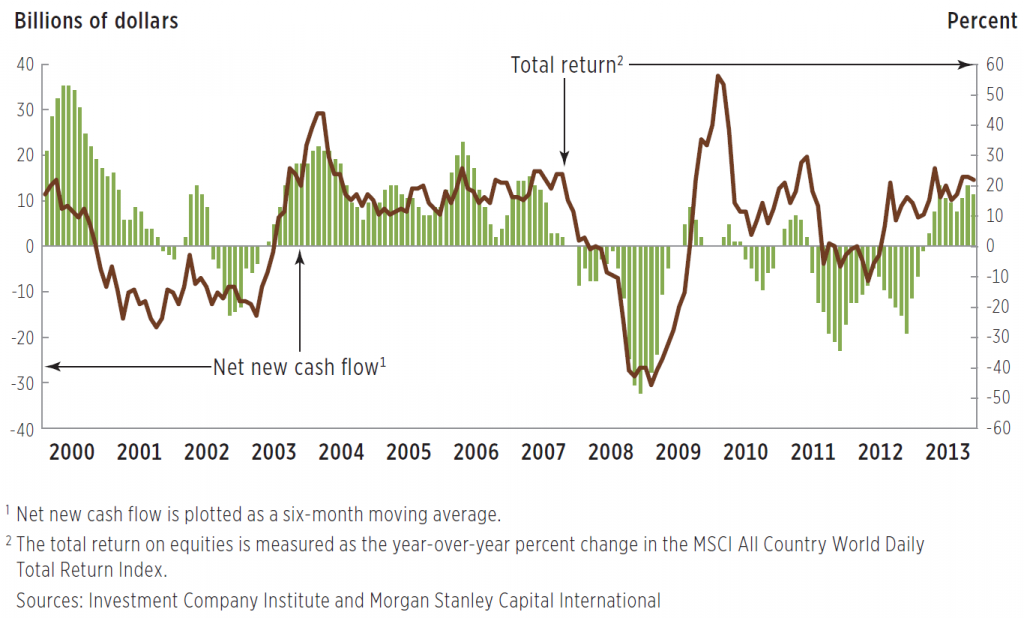

Observing peers is often a great way to learn. It’d be eye opening to see how well other fellow investors time the market, wouldn’t it?. Fortunately, this is possible. And based on hard data. The chart below shows inflows to equity funds (green bars) vs world equity returns (red line).

Notice how much inflows correlate with returns. What does it mean? Retail investors buy once markets have peaked (or are about to). And sell after markets crash. Simply put: retail investors buy high and sell low.

It’s kind of amusing to look at the chart. How can they do so poorly, right? I mean, we’ve all read Buffet’s quote. “Be fearful when others are greedy and greedy when others are fearful“. Easy-peasy. How can they still get it consistently wrong? Poor ignorants.

Well, get this in your head: you‘re one of them. At least if you try to time the market. You thought nobody else saw how easy it is to buy low and sell high, but you do, uh? What’s exactly makes you think that you’ll do better? You might be an educated person. Bachelor’s, master’s degree, languages, you name it. Is that really enough to think that you’re different? How exactly are you going to do better? Do you have access to better information? Better resources? A better intuition? Are you truly better at making rational choices? At separating emotions from investing? You aren’t.

A lot of people with high IQs are terrible investors because they’ve got terrible temperaments. You need to keep raw, irrational emotion under control

Charlie Munger

If you try to time the market, you’ll fall prey of the same psychological traps others have. Your emotions will take over. You’ll get greedy when others are greedy, and fearful when others are fearful. You’ll get it wrong as well.

Perspective 2: Waiting for the right time

This is one of the most patent examples of market timing I’ve seen. People try to optimize and ‘wait for the right time’ to invest. These are normally educated people. People who have capacity to invest, but lack the willingness to take financial risks. People who hoard 5-6 figures in cash (beyond their emergency funds).

Defining ‘the right time’

For these people, ‘the right time’ often means ‘after a market crash’. It’s a time when it’s obvious that it makes sense to invest. A time when there’s only upside. But it’s not priced in. In essence, a time that doesn’t exist. When there’s only upside, valuations will be high already. When stocks are cheap, there will be reasons for it. Reasons that will inevitably make these people even more risk averse.

A typical conversation

Market timers who wait for ‘the right time’ normally have no investment strategy whatsoever. This becomes apparent if you keep asking how. Conversations normally go like this:

– So, are you still investing every month?

+ Yes, sure! I don’t change my investing strategy that often!

– Oh, I see. I’m personally now waiting to see lower prices. The market is so overpriced at the moment. I expect a crash soon.

+ Aha, interesting. And how low should the market go for you to enter?

– Mmm, good question. I’m not sure, I’ll just wait for a correction to make sure I don’t buy at a peak.

+ OK, but how big should that crash be? Would a 5% leg down prompt you to buy?

– Mmmmh I don’t think so. That doesn’t feel low enough. Maybe if there is a big crash like in 2008. That’d make for a nice entry point.

+ I see. And how much would you buy at which levels?

– Look, I don’t know. I just feel like I shouldn’t invest now. Better when the markets bottom.

The lack of a systematic investment strategy

Needless to say, investment choices of those who time the market this way are dominated by feelings. And their overall strategy can be summarized in one word. Gambling. Do you really believe someone with such a strategy will make any money long term? Even if that person gets it right, they might be waiting 4 years for a crisis to invest 10k. During a true crisis, they’ll be scared to invest more anyways. So, even if they get it right, they might make a profit of 3k. Is this a serious approach to investing? A consistent, systematic approach that you can use throughout your life? I don’t think so.

Far more money has been lost anticipating bear markets than in bear markets

Peter Lynch

Timing the market by waiting for a crash is detrimental for your net worth. It prevents you from having a systematic investment strategy. And consistent and systematic win long-term. How should you invest then? Research from Vanguard indicates that, “on average, an immediate lump-sum investment has outperformed systematic implementation strategies”.

This means that the earlier you put all money you want to invest in the market, the better. There’s no point in waiting. You can dollar-cost average if it gives you some psychological relief. But you shouldn’t wait.

Perspective 3: Losing the fear to get it wrong – meet Bob

This is an interesting thought experiment proposed by Ben Carlson. It helps to lose the fear of investing at the wrong time.

What if you always got it wrong? What if you only invested lump sums right before a market crash? That’d be devastating, right? Well, it wouldn’t. At least not if you’re a long term investor and you never sell. Meet Bob.

Bob began his career in 1970 at age 22. He was a disciplined saver. He managed to set aside 2k per year in the 70s. And to bump that figure by 2k per year each decade.

Bob invested the money he saved. And whatever he bought, he never, ever, sold. Bob didn’t buy that often, though. In fact, he only made four purchases in his life. Bob was extremely unlucky. Every single time he invested was followed by a huge market crash:

| Date of investment | Amount invested (USD) | Subsequent crash |

|---|---|---|

| December 1972 | 6,000 | -48% |

| August 1987 | 46,000 | -34% |

| December 1999 | 68,000 | -49% |

| October 2007 | 64,000 | -52% |

| Total invested | 184,000 |

Poor Bob. What a terrible choice to invest. It must have killed all his savings, right? No, it didn’t. In fact, Bob retired at age 65 in 2013 as a millionaire. The value of his investments then was $1.1m. That’s ~6 times the total invested amount of $184k. How is this possible? Well, despite the market crashes, Bob never sold. Time did the rest.

Time in the market beats timing the market

What if Bob had dollar-cost averaged by buying yearly instead of just four times? He’d have ended up with $2.3m.

This thought experiment teaches you that you can’t be wrong enough to lose money investing. Not if you hold a diversified portfolio over the long run. So lose your fear. Start investing. Avoid market timing. Never sell. And stay the course long term.

Perspective #4: You can’t afford to miss out

Staying out of the market may result in you missing out. Big time.

What happens if you miss out on the best days

How can we quantify the long term loss of missing out? A common way is to see the impact on long term returns of staying out of the market on the best n days. This is a very selective analysis, but still gives food for thought.

Though tempting, trying to time the market is a loser’s game. $10,000 continuously invested in the market over the past 20 years grew to more than $48,000. If you missed just the best 30 days, your investment was reduced to $9,900

Christopher Davis

Let’s do our own analysis and come up with more data points. What if we had missed just 1 day? 3? 5? 10? We’ll use the S&P 500 total return index to find out. Data is publicly available here. We’ll set the time horizon to 30 years: from end of March 1990 to end of March 2020. How would our CAGR (that is, our annualized return) be impacted had we missed out on the greenest days?

The sensitivity of CAGR to the number of days missed is huge. Missing out on just one day lowers the CAGR from 9.3% to 8.9%. Miss out on the best 5 days and you CAGR is almost 2 full percentage points down.

Let’s look a it a bit differently. Assume we invested a lump sum of $10k in March 1990. What would be the portfolio value 30 years later?

Notice the huge gap between n = 0 and n = 3. A 40k difference! Almost 30% down! The lesson learned is that you might pay a big price for staying out of the market.

When do ‘best days’ happen anyways?

Are you curious what were the ten best days in the past 30 years?

| Rank | Date | Return |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 13 Oct 2008 | +11.6% |

| 2 | 28 Oct 2008 | +10.8% |

| 3 | 24 Mar 2020 | +9.4% |

| 4 | 13 Mar 2020 | +9.3% |

| 5 | 23 Mar 2009 | +7.1% |

| 6 | 13 Nov 2008 | +6.9% |

| 7 | 24 Nov 2008 | +6.5% |

| 8 | 10 Mar 2009 | +6.4% |

| 9 | 21 Nov 2008 | +6.3% |

| 10 | 26 Mar 2020 | +6.2% |

I find it interesting that three out of the ten literally just happened. Guess what happened to those who decided to time the market during the COVID-19 outbreak and got it wrong. Would you have anticipated a daily return of +9.3% on 13 Mar 2020? Or +9.4% nine days later? I don’t think so.

Best days tend to come when volatility picks up. Which is exactly the time when investors try to time the market the most. And when they miss out the most.

Perspective 5: The issue of replicability

You’ll often hear others boasting about their latest instance of great market timing. “It was clear that this was coming. That’s why I sold everything end of last year”. “I knew it was the time to get in”. Does it ring a bell?

Let’s get it straight: some people are simply going to get it right. They’ll sell before a crash, or buy before markets soar. But can they consistently get it right? Is this replicable?

A ‘gambling’ thought experiment

I find it interesting to draw parallels with gambling. Think about playing roulette in the casino. Say you and seven other friends go and play. Each of you is willing to bet $500. You just play colors: red or black. If each of you plays twice, statistically one of you will leave the casino with $4,000. That person got it right. Or did she?

She didn’t. Success or failure are not always the best indicators of whether a strategy is good or bad. Not in the short run. Not with few instances. Being successful at the roulette doesn’t mean you had a winning strategy.

Similarly, occasionally being successful at market timing doesn’t make one a good market timer. And market timers are right occasionally at best. From the outside it might look like they’re doing great. But that’s just because they won’t tell you when they got it wrong. Those instances are swept under the rug. The important aspect isn’t whether they got their last bet right. It’s whether they can consistently get it right. If what they’re doing is replicable. They’d be billionaires if it was, as we’ll see in perspective #6.

The individual investor should act consistently as an investor and not as a speculator

Benjamin Graham

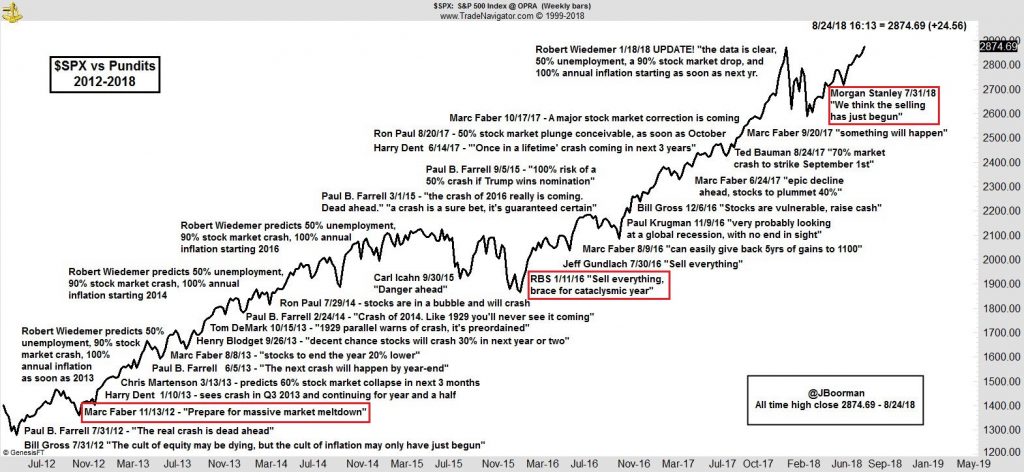

Predicting market movements

The same line of thought applies to pundits who predict market movements. There will always be someone who predicted the next crash. 100% sure. How do I know? Well, because there’s thousands of predictions being made every day. Every day someone predicts a market crash happening soon. All possible scenarios are covered. Someone will eventually get it right. Most will get it wrong.

Mutual funds can’t keep up either

The same line of thought applies once again to mutual funds outperformance. It’s simply not replicable. The chart below shows the percentage of mutual funds outperforming their benchmark, net of fees. Notice that for a 1-year period it’s bad enough already. Just 35% outperform their benchmark. But even those 35% can’t keep up. For a 15-year period, just 5% outperform. What implies that 95% underperform.

Data for the chart comes from different sources [2, 3], so take it as illustrative only. In my view it makes a big point, though.

Try if you dare

How consistently can you time the market? It’s easy to conduct an experiment. You can use Investopedia’s stock simulator. Put your foresight on the spotlight without risking real money. Try to time the market in a systematic and consistent way. And keep score. You want to make sure whatever you do is replicable with real money.

Perspective 6: Let’s assume you can time the market

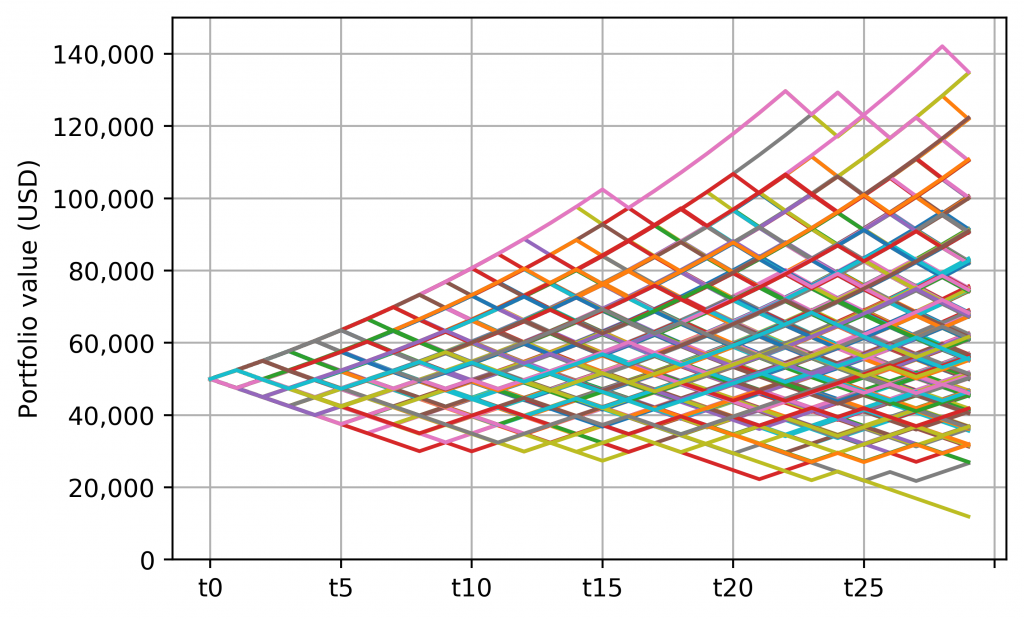

Let’s imagine for a moment that you can time the market. You acknowledge your limitations, though. There’s no way you’ll get it right 100% of the time. But still you feel like you can do better than simply riding the market’s ups and downs. Say you can get it right 60% of the time.

If you believe this, I have good news! You have a money machine! You just have to spread your bets enough for the law of large numbers to kick in. How much is that? We’ll, let’s make some assumptions and run a monte carlo simulation.

The assumptions

- Starting capital: CHF 50k

- Investment %: variable to optimize for. Percentage of available capital that you commit each time you invest

- Gain/loss: to make it simple, let’s say you use options. Each time to invest, either you lose your investment or you double up (gross of fees)

- Transaction fees: 1% of each invested amount

- Number of bets: 30 times per year (once every ~2 weeks)

- Number of simulations: 1,000

The outcome

The table below contains the output after running 1,000 simulations. Each row explores a different value for investment %. This is the % of our capital committed each time we invest:

| Investment % | Prob. of losing everything | Prob. of losing money | Median ending value | Average ending value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 100% | 100% | 100% | 0 | 0 |

| 70% | 65% | 87% | 0 | 1.6m |

| 50% | 26% | 63% | 17k | 550k |

| 20% | 0% | 35% | 108k | 150k |

| 10% | 0% | 21% | 84k | 88k |

| 5% | 0% | 13% | 62k | 66k |

Obviously the all-in strategy (investment = 100%) isn’t a good idea. With just a 60% success rate, it’s only a matter of a few trials until we go bust. Investing 70% or 50% of our capital each time is also too much. We need to spread our bets further to be statistically safe. At 5%, it’d be very unlikely to go bust. The probability of ending with less capital than we started is 13%. And we lock in a ~32% expected profit after a year.

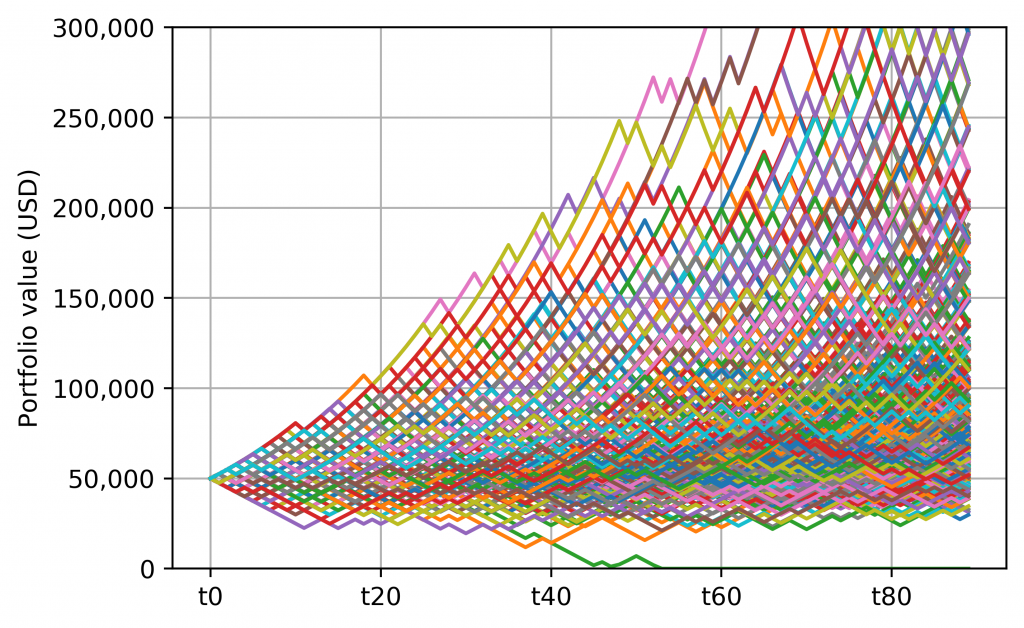

Just keep going!

The chart above captures just a year worth of work. If we keep going, soon we’ll see exponential growth. Let’s see what happens if we continue over two more years (three years in total).

Now we’re talking! If we get it right 60% of the time and invest 5% of our capital each time, it’s extremely unlikely that we’ll lose any money. Not even after paying 1% fees each time. Just one simulation out of 1,000 went bust. Pretty much all others are doing great. In fact, your expected total return after three years is ~120%. That’s a 30% CAGR. If this was possible, I’d definitely quit my job and start investing full time. Wouldn’t you?

The moral

This long analysis proves a simple point: anyone who could truly time the market would have a money machine. Do you know anyone with a money machine? Also, active funds would constantly outperform their benchmark. Do they?

If anyone had the ability to time the market, that person would quickly become a billionaire

Last updated on November 2, 2020

One reply on “Market timing and perspectives on why to avoid it”

Amazing articles and blog. Best summary of the basics of investing in a structured and clear way. Thank you so much !