More than half of the world’s equity market is American [1]. This makes it very common to invest in funds holding American companies. These companies trade in USD. Most earn revenues in multiple currencies: USD, JPY, EUR, CNY etc. On top of that, the fund itself may trade in CHF or EUR. How does it all play along?

FX exposure

The Foreign Exchange (FX) market is the global marketplace that determines the exchange rate for currencies around the world [2]. FX exposure, FX risks, currency exposure and currency risks are all synonyms. They all are the risk of change in value of your foreign assets in your domestic currency [3]. This happens due to fluctuations in exchange rates.

Currency risks are largely unavoidable. If you’re an expat, chances are that you have a decent FX exposure already (unless you’re from Liechtenstein). This is because the value of your Swiss francs (CHF) in your country’s original currency – where you might still have expenses due to family, property, vacations etc. – fluctuates on a continuous basis.

Investing brings FX risks to a new level. Let’s find out why.

A quick refresher on exchange rates

Currency exchange rates are expressed as a pair of currency symbols one after the other. They might or might not be separated by a slash ‘/’. The rate indicates how many units of the second currency you get per unit of the first.

For example, an exchange rate of USDEUR = 0.93 means that you get 0.93 EUR per 1 USD. The USD is weaker than the EUR, because 1 USD buys you less than 1 EUR. If USDEUR goes up, the USD is appreciating, because now 1 USD buys you more EUR.

We can also flip the way we look at it. An exchange rate of EURUSD of 1.08 (1/0.93) means that you get 1.08 USD per 1 EUR. The EUR is stronger than the USD, because 1 EUR buys you more than 1 USD. If EURUSD goes up, the EUR is appreciating, because now 1 EUR buys you more USD.

This can be a bit confusing at first. Especially if you’re not used to FX notation. Don’t feel bad if you have to read the paragraphs above again to get it. The key is to remember that an FX rate indicates how many units of the second currency you get per unit of the first.

Are you comfortable with FX notation? Let’s move on then.

Buying foreign indices in a foreign currency

Say that we’re interested in buying a fund that tracks the S&P 500. The S&P 500 is a market capitalization-weighted average of the prices of the largest 500 US companies. All US companies trade in USD. And hence the S&P 500 is calculated in USD.

The trivial way to invest is to buy a S&P 500 ETF denominated in USD. But the currency you use in your daily life might not be USD. Assume it’s CHF. The value of your investments, in CHF, now depends on the CHFUSD FX rate.

What does this mean? Imagine the S&P 500 total return ends up being 0.0% in a given year. The value of your ETF in USD will experience no change. In CHF, this is not necessarily true:

- If the USD appreciated, then you have made money in CHF terms

- If the USD depreciated, then you have lost money in CHF terms

Buying foreign indices in your local currency

We can also find an ETF that tracks the S&P 500 in our local currency (CHF). This could be a good candidate. Problem solved? Not really.

The base currency of the fund is still USD. It doesn’t matter whether it trades in CHF, EUR or Russian rubles. Why? Because the trading price in any currency is simply continuously converted from USD. Your FX risk is exactly the same as in the previous case, when you were buying directly in USD. Only that now you see the value of your investments converted continuously.

Don’t let the trading currency fool you. It’s the currency of the fund that matters.

What’s the impact of currency risks?

Alright, we got it. It’s the currency of the fund that matters. Not the currency it trades in. If the currency of the fund is distinct from ours, we’re exposed to FX risks. But how big are these risks anyways? Let’s look at the past.

The CHF has strongly appreciated against the USD over the last 30 years. Particularly in the decade of the 2000s. In January 2000, 1 CHF would buy you 0.6 USD. In December 2009, 1 CHF would buy you 0.97 USD. This is roughly 60% more dollars than at the beginning of the decade!

Had you invested in an ETF with base currency USD in 1990, your return in CHF would have been strongly damped by the appreciation of the CHF. Why? Because the amount of CHF you got per USD was decreasing.

If that makes to you, the following chart should be a piece of cake:

The blue line is the price of the S&P 500 in USD. The red line is the price of the S&P 500 in CHF. Because the CHF was appreciating, less CHF were needed to hold the same value. The compound annual return (CAGR) over the ~30-year period was ~7.8% in USD. But only ~6.1% in CHF. Lesson learned: you don’t want the CHF to appreciate when you’re buying assets in other currencies!

Should I bet on currencies as part of my investment strategy?

The example we just saw sucks. You’d have been better off by not holding dollars. The obvious conclusion is that we should be smart and try to anticipate FX moves, right? No! You shouldn’t bet on a currency appreciating or depreciating against others. Why? Simply put, because you can’t get it right. Because of its size, the FX market is a paradigm of the efficient market hypothesis (EMH). The EMH theorizes that, at any point, asset prices reflect all available information. You might think that it’s smart to buy or sell currency X. But chances are that you don’t really have better knowledge than that already priced in the current rate. In fact, most likely you know worse. If you bet on currencies, chances are you’re just gambling.

It would also be a bad strategy to simply avoid all currency risks in your portfolio by only investing in local securities. American equities, for example, are by far the biggest equity market in the world. It wouldn’t be smart to just neglect them.

Besides, if we focus on the past 8-10 years, the CHFUSD rate has been relatively stable. The currency effects on your investments would have been minor:

Currency-hedged ETFs

You might still feel unhappy about the effect that FX rates have on your investments. After all, it adds another layer of uncertainty to the already volatile equity returns. If all I care about is the market value of my portfolio in my local currency (say Swiss francs), currency moves just add noise. This is the reason why, for some time, I was a big fan of currency-hedged ETFs.

Currency-hedged ETFs shield investors from currency risks. How? By effectively changing the base currency of a fund. This sort of eliminates FX risks.

To put it very pragmatically, if we look at the S&P 500 examples above, a currency-hedged ETF would allow you to replicate the returns from the original S&P 500 (in USD), but in CHF. In other words, your investment results in CHF would not have been the red line, but the blue one (less fees of course). This is achieved at a fund level through the use of more complex financial instruments (derivatives).

Although they’re very attractive at first sight, currency-hedged ETFs also have their drawbacks.

Why currency-hedged ETFs don’t completely eliminate FX risks

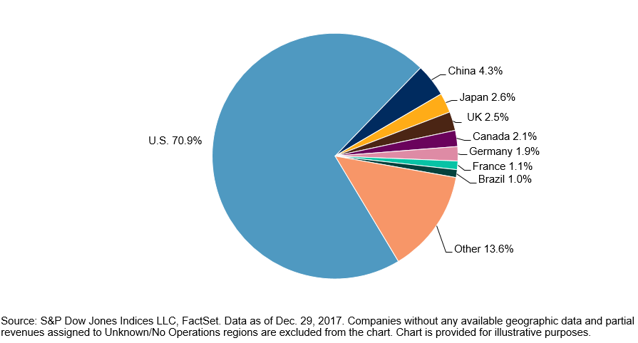

Currency-hedged ETF only hedge stock prices. That’s not enough. Currency risks cannot be fully eliminated because multinational companies (like those in the S&P 500) earn their revenues globally. And globally implies in multiple currencies:

What does this mean? What happens to your investments in US companies when the CHFUSD fluctuates?

Let’s analyze all possible scenarios. If the CHFUSD changes, it must be driven either by an appreciation/depreciation of the USD (think about the USD becoming stronger/weaker against all other major currencies) or an appreciation/depreciation of the CHF (think about the CHF becoming stronger/weaker against all other major currencies). In reality it’s always because of a combination of the two. But let’s keep it simple.

A stronger/weaker CHF

Assume it’s CHF the one driving the change. In this case, the currency hedge will be quite efficient. Why? Because the fraction of the total revenues that S&P 500 companies earn in CHF is minimal. Likely less than 1% if we trust the pie chart. Because S&P 500 revenues are relatively insensitive to what happens to the CHF, the price of the S&P 500 itself is insensitive as well.

OK, so a stronger or weaker Swiss franc doesn’t affect that much the price of the S&P 500. But how much does it affect the value of your portfolio? A lot. At least in CHF terms. Remember that you’re holding USD but care about CHF. You have to convert USD back to CHF. And that’s by definition affected by the Swiss franc being stronger or weaker.

A currency hedge will protect you against a loss of value if the CHF is appreciating. Conversely, a currency hedge will nullify a gain in value if the CHF is depreciating. So far so good for our currency-hedged ETF. It works.

A stronger USD

The story is very different when it’s the USD the currency driving the change in the CHFUSD rate. Why? Because the price of the S&P 500 is very sensitive to the value of the USD.

A global appreciation of the dollar makes American companies less competitive vs other global players. Think about it. When the dollar appreciates, the prices of the products and services sold by American companies become relatively high in other currencies. And there’s not so much they can do to lower prices.

When large, multinational American companies become less competitive, the S&P 500 tends to fall. Your currency-hedged ETF falls along. In a way, it’s failing to protect you against a ‘currency risk’.

Moreover, the currency hedge is also cancelling the offsetting effect that a stronger dollar would have in the CHF value of your investments. Without the hedge, even if the S&P 500 falls, you’d be getting more CHF per USD as the dollar appreciates. With the hedge, you don’t.

A weaker USD

To be fair, let’s consider the opposite case. A global depreciation of the USD results in American companies being more competitive. The S&P 500 could soar. With the hedge, you’ll not only benefit from the S&P 500 soaring. You’re eliminating the decrease in value from a weaker USD when you translate to CHF. Without the hedge, the S&P 500 gain would be partially offset by a weaker dollar when converting to CHF.

Summary on currency-hedging

Let’s summarize what we’ve seen so far for our CHF-hedged ETF:

- CHF appreciates: hedge works as expected and stops the value loss

- CHF depreciates: hedge works as expected and cancels the value gain

- USD appreciates: hedge doesn’t work, you suffer a disproportionately big value loss

- USD depreciates: hedge doesn’t work, you enjoy a disproportionately big value gain

In a nutshell, the hedge works for CHF moves. But not for USD moves. In fact, it amplifies gains/losses, in CHF terms, if the USD fluctuates. Because of this, the way I see it, buying currency-hedged ETFs implies to some degree taking a view on exchange rates. Which is something to avoid.

It’s even more complex…

In reality, multinational companies also have their own currency hedges in place. This only complicates things further. For a broad index like the S&P 500, knowing exactly what’s the aggregated effect of these hedges is impossible. In a nutshell, you can’t never fully eliminate FX risk.

The real cost of currency-hedged ETFs

Currency-hedged ETFs can’t fully eliminate FX risks. Unfortunately, there are even more negative surprises. Currency-hedged ETFs are also more expensive than you think.

What’s the real cost of hedging?

Currency-hedged ETFs tend to have higher TERs than their non-hedged counterparts. The difference is often in the order of ~20-30bps. This makes sense if you take into account the additional management they require. However, the higher TER is just the tip of the iceberg. The true cost of currency hedging comes from elsewhere.

Currency-hedged ETFs use forward contracts to hedge against FX fluctuations. This cost is passed to investors. Where is this cost?, you may ask. Isn’t it part of the TER? The answer is no. The main cost of currency-hedged ETFs is that they don’t track an index (e.g. S&P 500). They track a hedged version of the index. And returns differ.

To illustrate, look at the investment objective of this CHF hedged ETF:

The Fund seeks to track the performance of an index composed of 500 large cap U.S. companies which also hedges USD currency in the index back to CHF on a monthly basis.

What’s the impact of tracking a hedged index?

Let’s compare the total returns of this ETF with those of a popular US domiciled ETF that trades in USD (Vanguard’s VOO):

| Year | Returns of US domiciled ETF¹ | Returns of CHF-hedged alternative² | Delta |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2019 | +31.47% | +26.72% | -4.75% |

| 2018 | -4.47% | -8.36% | -3.89% |

| 2017 | +21.74% | +18.34% | -3.40% |

| 2016 | +12.04% | +8.75% | -3.29% |

| 2015 | +1.32% | -0.31% | -1.63% |

¹ Vanguard S&P 500 ETF (VOO)

² iShares S&P 500 CHF Hedged

A tiny part of the difference might come from VOO’s lower TER (3 vs 20bps). But what is that difference compared to the full -3.4% average lower returns per year?

Why are the returns of the hedged index lower?

At the moment, hedging USD to CHF is extremely expensive. Why is this? Without getting into much detail, the cost of hedging currencies depends on the spread in interest rates of government bonds in the different currencies.

Cost to hedge USD to CHF ~= interest rate in USD – interest rate in CHF

Interest rates in the US are higher than in Switzerland. They’re also higher than in Europe. This has been the case for 10+ years.

As you can see, EUR and CHF interest rates have been for a while zero or negative. You may remember from primary school what happens when you subtract a negative number. Now look at the equation above for the cost of hedging. US rates being higher than Swiss/European rates explains the current high cost of hedging. I say current, because this could reverse in the future.

What the hell should I do?

Props if this is what you’re thinking. It means that you’ve been following. So far no option seems to be ideal.

The options

We’ve explored three options to invest into US stocks:

- US domiciled funds

- US funds in our local currency

- US funds currency-hedged to our local currency

The first two imply taking on full currency risks. The last one is unreasonably expensive and doesn’t always work. By the way, there are no more options. What should you do?

The answer

Honestly, there’s none. At least not an answer that is valid for everyone. You’ll have to make up your mind yourself. What I can do is provide some food for thought in the form of two general investing guidelines:

- When investing long term, you should always minimize recurring costs

- In general, you want the currency of your wealth to be aligned with the currency of your future expenses

The first guideline always points in the same direction: option 1. Accept full FX risk and buy US domiciled funds. They’re more optimal from a tax and fees perspective, as discussed here.

The second guideline is trickier. If you’re absolutely sure that you’ll spend the rest of your life in Switzerland, you might want to mitigate FX risks. After all, how useful are dollars to you? Why be exposed to them more than necessary? You probably shouldn’t. But at the same time you shouldn’t neglect US equities. Currency-hedged ETFs might be a good choice. At least for a fraction of your portfolio. They won’t fully protect you against currency swings, but will protect you against appreciation of the CHF.

More commonly, however, you simply don’t know. Especially if you’re an expat. If this is your case (it’s mine), I’d argue that the risk of holding your wealth in USD is somehow mitigated. USD is a much more global currency than CHF after all. It’s a good hedge against uncertainty. I wouldn’t be too afraid to hold USD denominated ETFs.

My personal choice

I for once only hold US ETFs. That means that my whole portfolio trades in dollars. I acknowledge however that there is some inherent risk in having most of my wealth in USD. Currently I live in Switzerland, which means that I have recurrent expenses to pay for in Swiss francs (rent, food etc.). I also take holidays in southern Europe, where I pay for stuff in euros. If I ever want to finance my expenses off of my portfolio, I’ll be exposed to exchange rates. I choose to accept the currency risk. Why? Mostly because I consider my investment horizon long enough for the tax and fees advantages of US funds to outweigh currency risks.

But in the end this is a personal assessment. If you’d like to learn more about my personal assessment, you should check this post.

A word on bonds

This entry focused on equity ETFs (e.g. S&P 500). If you’re interested in bonds, the picture looks a bit different. Hedging bonds might make sense in principle, because:

- With bonds, there are no underlying revenues in different currencies. This means that currency effects have no impact on cash flows.

- FX volatility is typically in higher than bond yields. In other words, FX volatility prevents you from having predictable returns

The problem is that hedging will be expensive when foreign interest are attractive. And cheap when they’re not. Just think about the equation for cost of hedging. At the moment, for example, hedging is expensive. There’s no point in buying hedged US bonds with a yield to maturity of 2.5% if you have to pay 3% in hedging costs.

At the same time, investing in foreign bonds without hedging makes little sense. In general, when you buy bonds you’re looking for predictable returns. How predictable can my CHF returns be if I’m exposed to exchange rates? FX rates can easily change by 10% in a year. Are you willing to take that risk for your bond portfolio? Likely not.

The final option is to invest in domestic bonds. But Swiss bonds have a negative yield to maturity. You lose money by buying them.

See the struggle? At least with equities we had some fair options. As Swiss investors, with bonds we don’t.

Last updated on June 14, 2020

One reply on “FX exposure and currency-hedged ETFs”

Awesome summary! I was always avoiding hedged ETFs mostly because of costs and lower performance but your reasoning about insufficient protection in certain cases is really good.